Toxoplasma gondii

| Toxoplasma gondii | |

|---|---|

|

|

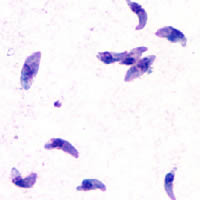

| T. gondii tachyzoites | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Chromalveolata |

| Superphylum: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Conoidasida |

| Subclass: | Coccidiasina |

| Order: | Eucoccidiorida |

| Family: | Sarcocystidae |

| Genus: | Toxoplasma |

| Species: | T. gondii |

| Binomial name | |

| Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle & Manceaux, 1908) |

|

Toxoplasma gondii is a species of parasitic protozoa in the genus Toxoplasma.[1] The definitive host of T. gondii is the cat, but the parasite can be carried by many warm-blooded animals (birds[2] or mammals). Toxoplasmosis, the disease of which T. gondii is the causative agent, is usually minor and self-limiting but can have serious or even fatal effects on a fetus whose mother first contracts the disease during pregnancy or on an immunocompromised human or cat.

Contents |

Life cycle

The life cycle of T. gondii has two phases. The sexual part of the life cycle (coccidia like) takes place only in members of the Felidae family (domestic and wild cats), which makes these animals the parasite's primary host. The asexual part of the life cycle can take place in any warm-blooded animal, like other mammals (including felines) and birds.

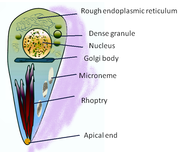

In the intermediate hosts (as well the definitive host, felines), the parasite invades cells, forming intracellular so-called parasitophorous vacuoles containing bradyzoites, the slowly replicating form of the parasite.[3] Vacuoles form tissue cysts mainly within the muscles and brain. Since they are within cells, the host's immune system does not detect these cysts. Resistance to antibiotics varies, but the cysts are very difficult to eradicate entirely. Within these vacuoles T. gondii propagates by endodyogeny until the infected cell eventually bursts and tachyzoites are released. Tachyzoites are the motile, asexually reproducing form of the parasite. Unlike the bradyzoites, the free tachyzoites are usually efficiently cleared by the host's immune response, although some manage to infect cells and form bradyzoites, thus maintaining the infection.

Tissue cysts are ingested by a cat (e.g., by feeding on an infected mouse). The cysts survive passage through the stomach of the cat and the parasites infect epithelial cells of the small intestine where they undergo sexual reproduction and oocyst formation. Oocysts are shed with the feces. Animals and humans that ingest oocysts (e.g., by eating unwashed vegetables etc.) or tissue cysts in improperly cooked meat become infected. The parasite enters macrophages in the intestinal lining and is distributed via the blood stream throughout the body.

Similar to the mechanism used in many viruses, Toxoplasma is able to dysregulate host’s cell cycle by holding cells at the G2/M border.[4] This dysregulation of the host’s cell cycle is caused by a heat-labile factor that is larger than 10kDa.[5] Infected cells secrete the factor which inhibits the cell cycle of neighboring cells. The reason for Toxoplasma’s dysregulation is unknown, but studies have shown that infection is preferential to host cells in the S-phase and host cell structures with which Toxoplasma interacts may not be accessible during other stages of the cell cycle.[6] [7] [8] [9] [10]

Acute stage Toxoplasma infections can be asymptomatic, but often give flu-like symptoms in the early acute stages, and like flu can become, in very rare cases, fatal. The acute stage fades in a few days to months, leading to the latent stage. Latent infection is normally asymptomatic; however, in the case of immunocompromised patients (such as those infected with HIV or transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy), toxoplasmosis can develop. The most notable manifestation of toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients is toxoplasmic encephalitis, which can be deadly. If infection with T. gondii occurs for the first time during pregnancy, the parasite can cross the placenta, possibly leading to hydrocephalus or microcephaly, intracranial calcification, and chorioretinitis, with the possibility of spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) or intrauterine death.

Toxoplasmosis

T. gondii infections have the ability to change the behavior of rats and mice, making them drawn to rather than fearful of the scent of cats. This effect is advantageous to the parasite, which will be able to sexually reproduce if its host is eaten by a cat.[11] The infection is highly precise, as it does not affect a rat's other fears such as the fear of open spaces or of unfamiliar smelling food.

Studies have also shown behavioral changes in humans, including slower reaction times and a sixfold increased risk of traffic accidents among infected males[12], as well as links to schizophrenia including hallucinations and reckless behavior[13]. Additionally, studies of students and conscript soldiers in the Czech Republic in the mid-1990s highlighted the fact that infected people showed different personality traits to uninfected people—and that the differences depended on sex. Infected women were more likely to become more outgoing and showed signs of higher intelligence, while men became aggressive, jealous and suspicious.[14]

The prevalence of human infection by Toxoplasma varies greatly between countries. Factors that influence infection rates include diet (prevalence is possibly higher where there is a preference for less-cooked meat) and proximity to cats. It has been suggested that climate change will also influence Toxoplasma gondii prevalence in some regions of the world.[15]

History

The organism was first described in 1908 in Tunis by Charles Nicolle and Louis Manceaux within the tissues of the gundi (Ctenodactylus gundi). In the same year it was also described in Brazil by Alfonso Splendore in rabbits .

References

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (eds) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 722–7. ISBN 0838585299.

- ↑ Dubey JP, Webb DM, Sundar N, Velmurugan GV, Bandini LA, Kwok OC, Su C. (2007-09-30). "Endemic avian toxoplasmosis on a farm in Illinois: clinical disease, diagnosis, biologic and genetic characteristics of Toxoplasma gondii isolates from chickens (Gallus domesticus), and a goose (Anser anser)". Vet Parasitol. 148 (3-4): 207–12. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.06.033. PMID 17656021.

- ↑ Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Speer CA (1 April 1998). "Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11 (2): 267–99. PMID 9564564. PMC 106833. http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/content/full/11/2/267?view=long&pmid=9564564.

- ↑ Ira J. Blader, Jeroen P. Saeij. Communication between Toxoplasma gondii and its host: impact on parasite growth, development, immune evasion, and virulence. APMIS 2009:117: 458-476.

- ↑ Lavine MD, Arrizabalaga G. Exit from host cells by the pathogenic parasite Toxoplasma gondii does not require motility. Eukaryotic Cell 2008;7:131–40.

- ↑ Dvorak JA, Crane MS. Vertebrate cell cycle modulates infection by protozoan parasites. Science 1981;214:1034–6.

- ↑ Grimwood J, Mineo JR, Kasper LH. Attachment of Toxoplasma gondii to host cells is host cell cycle dependent. Infect Immun 1996;64:4099–104.

- ↑ Youn JH, Nam HW, Kim DJ, Park YM, Kim WK, Kim WS, et al. Cell cycle-dependent entry of Toxoplasma gondii into synchronized HL-60 cells. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi 1991;29:121–8.

- ↑ Coppens I, Dunn JD, Romano JD, Pypaert M, Zhang H, Boothroyd JC, et al. Toxoplasma gondii sequesters lysosomes from mammalian hosts in the vacuolar space. Cell 2006;125:261–74.

- ↑ Walker ME, Hjort EE, Smith SS, Tripathi A, Hornick JE, Hinchcliffe EH, et al. Toxoplasma gondii actively remodels the microtubule network in host cells. Microbes Infect 2008;10:1440–9.

- ↑ Berdoy M, Webster JP, Macdonald DW (August 2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proc. Biol. Sci. 267 (1452): 1591–4. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMID 11007336. PMC 1690701. http://journals.royalsociety.org/openurl.asp?genre=article&issn=0962-8452&volume=267&issue=1452&spage=1591.

- ↑ Flegr J, Klose J, Novotná M, Berenreitterová M, Havlíček J (2009). "Increased incidence of traffic accidents in Toxoplasma-infected military drivers and protective effect RhD molecule revealed by a large-scale prospective cohort study". BMC Infectious Diseases 9 (72): 72. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-9-72. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/9/72.

- ↑ http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427301.600-3-schizophrenia.html

- ↑ Adam, David (2003-09-25). "Can a parasite carried by cats change your personality?". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2003/sep/25/medicineandhealth.thisweekssciencequestions1. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Meerburg BG, Kijlstra A (2009). "Changing climate—changing pathogens: Toxoplasma gondii in North-Western Europe". Parasitology Research 105 (1): 17. doi:10.1007/s00436-009-1447-4. PMID 19418068. PMC 2695550. http://www.springerlink.com/content/6k40766145g56746.

External links

- ToxoDB : The Toxoplasma gondii genome resource

- Anti-Toxo : A Toxoplasma news blog and list of research laboratories

- Toxoplasma images, from CDC's DPDx, in the public domain

- Toxoplasmosis Research Institute & Center

- Cytoskeletal Components of an Invasion Machine — The Apical Complex of Toxoplasma gondii

- The Culture-Shaping Parasites, in Seed Magazine

- Sneaky Parasite Attracts Rats to Cats, All Things Considered, April 14, 2007

- Toxoplasma overview, developmental stages, life cycle image at MetaPathogen

- Toxoplasma lecture, Robert Sapolsky

- Could a brain parasite found in cats help soccer teams win at the World Cup? - By Patrick House - Slate Magazine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||